This post is also available in: Dutch (below)

Click here for the other articles of the series: Forest series

This series of articles was written and published in 2011 in the Antilliaans Dagblad newspaper. 2011 was the year that the United Nations declared the International Year of Forests, in order to give more attention to the “lungs” of the earth. Without forests, life on earth is impossible. The original series concerned the mondi of Curaçao and has been adapted and rewritten where necessary to also include the sister islands of Aruba and Bonaire. This is part 12 of the series, illustrating some of the dangers forests worldwide, including on the islands of Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire, face.

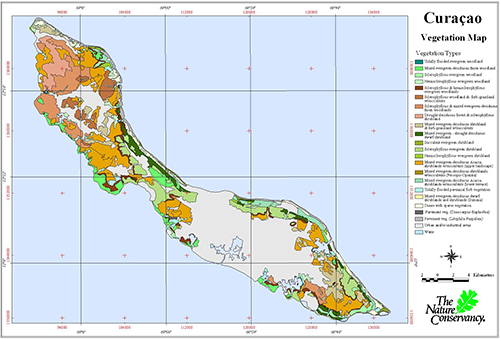

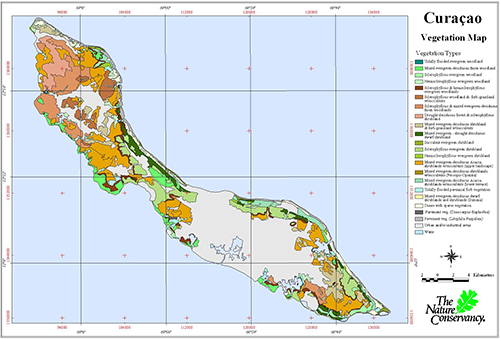

The disruption of natural processes is the final blow to forests. The isolation of small patches of nature, disrupting not only animals but also plants in their natural habitat, is a common occurrence on the ABC Islands. The Banda Bou region on Curaçao, for example, is (still) relatively undeveloped compared to the city. However, if you look at the map of the island, you’ll see that Banda Bou is also quite isolated from the rest of the island’s greenery. We, as residents of Curaçao, have effectively divided the island into two. There’s the relatively untouched natural area at Oostpunt, a fact that will likely soon be a thing of the past due to government plans, and there’s the section from Zegu to Westpunt, colloquially known as Banda Bou. If you look closely at the map, you’ll see that there’s essentially no connection between the two parts anymore. The airport in the central part of the island has effectively created a boundary, creating two separate areas. A number of small nature reserves remain between West and East, such as Rooi Rincon, the strip from there towards the Hato Caves, the Gnome Forest, the small Den Dunki, and the top of the hill in Rooi Santu, Seru di Seinpost. The Jan Thiel nature reserve could also be included, and perhaps the few gullies and patches of mondi that haven’t been built on. For birds, the long crossing from East to West may not be so dramatic, although it has never been proven that birds actually “travel” from one side to the other. However, it has also never been proven that this doesn’t happen. But anyone can bet that it’s much more difficult for plants and other animal species. The Curaçao white-tailed deer, unique to the Caribbean, is extinct on Banda Riba and now only occurs in Banda Bou. Several tree species can only spread thanks to the “unintentional” intervention of humans. In fact, we’ve all turned one island into two separate islands, in terms of nature.

Urbanization on the islands

This phenomenon is particularly evident on Aruba. The ultra-urbanized island has patches of nature that are relatively far apart and have little to no contact with each other. The Cottontail, a rabbit also found on Curaçao, and the Sloke, a primarily wandering bird, are becoming increasingly isolated as a result, resulting in little interaction between individuals of the same species, putting the species at risk due to factors such as inbreeding. Other animals and plants are also suffering from the formation of these so-called postage-stamp nature reserves, a term now widely used in Europe.

In biology, we speak of so-called corridor areas. These are areas that serve as a kind of “subway” for plants and animals, a place where they can find shelter and then make further migrations. It’s crucial that the distances from the corridor areas to the next location are not too big. If species can no longer use such a small nature reserve as a hub to the next location because the distance has become too big, it essentially loses its ecological value. It is then of little ecological value.

Besides suffering from the fragmentation of nature reserves, our forests also suffer from several other factors:

- pollution, due to chemical compounds such as oil;

- deforestation due to the continuous removal of land for building, both legally and illegally;

- alteration of natural water flows, meaning that during rainstorms, not enough water reaches the groundwater to build up reserves for inclement weather. Paving waterways and gullies is a particular disaster for the groundwater level;

- the introduction of plant species from abroad that crowd out or even strangle our own trees and plants, such as the Pal’i lechi (Rubbervine, Cryptostegia grandiflora) which suffocates trees, and the Korona di Hesus (Egyptian balsem, Balanites aegyptiaca), a species that is inconspicuous but very dangerously encroaching; – the introduction of animal species from abroad, such as the Red Palm Weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus) and Agave Weevil (Scyphophorus acupunctatus). This poses a threat not only to equally expensive foreign palms, but also potentially to the native Sabal Palm, the only palm species we naturally have on the island, and the Agave Weevil to our native agave plants.

The fact that Curaçao still has a semi-natural “island” on the West and an “island” on the East is small consolation. It becomes more pressing when we realize that even within these two “islands,” there is fragmentation and isolation. That we, as islanders, are so unconsciously “developing” everywhere that even within the small island of Banda Bou, isolated nature reserves will emerge, making the survival of the unique flora and fauna even more difficult.

In fact, you can compare nature and all the systems that function within it to a very expensive and unique Persian rug. The whole rug is worth its weight in gold. Cut it into pieces and sew it back together, and you could stand on your head, but you wouldn’t get a cent for it. Even if you didn’t lose anything and you had the whole rug back together. That’s how it is with nature. If it’s a continuous piece without any breaks, then it “works.” Cut it into pieces, and no matter how much you sew together, you’ll never get your “Persian rug” back.

Bossen op de semi-aride ABC-eilanden (13) – Bossen – nauurgebieden in gevaar

Deze artikelenserie werd in 2011 geschreven en gepubliceerd in het Antilliaans Dagblad. 2011 was het jaar dat door de Verenigde Naties werd uitgeroepen tot het internationaal jaar van de bossen, om zodoende de “longen” van de aarde meer aandacht te geven. Zonder bossen is leven op aarde namelijk onmogelijk. De oorspronkelijke serie betrof de mondi van Curaçao en is aangepast en waar nodig herschreven om ook de zustereilanden Aruba en Bonaire er ook in mee te nemen. Dit is deel 12 van de serie, met de gevaren waaraan bossen blootstaan.

Het verbreken van natuurlijke processen, dat is de nekslag voor bossen. De isolatie van kleine stukjes natuur waardoor niet alleen dieren, maar ook planten in hun natuurlijk leven worden verstoord is een gegeven dat je ook op de ABC-eilanden zeer veel ziet. De regio Banda Bou op Curaçao is bijvoorbeeld (nog) relatief onontwikkeld in vergelijking met de stad. Echter, als je op de kaart van het eiland gaat kijken dan zie je dat Banda Bou ook behoorlijk geïsoleerd is van de rest van het groen op het eiland. Wij hebben, als bewoners van Curaçao, gezorgd dat het eiland in feite in 2-en is opgedeeld. Je hebt het stukje natuur op Oostpunt, dat relatief onaangetast is, een gegeven dat waarschijnlijk binnenkort door plannen van de overheid ook tot het verleden hoort, en je hebt het stukje vanaf Zegu naar Westpunt, Banda Bou in de volksmond genoemd. Als je goed naar de kaart kijkt zie je dat er eigenlijk helemaal geen connectie meer is tussen de beide delen. De luchthaven in het centrale deel van het eiland heeft effectief een begrenzing ingesteld waardoor je twee van elkaar afgezonderde gebieden hebt gekregen. Tussen West en Oost zijn nog een aantal kleine natuurgebiedjes over zoals Rooi Rincon, de strook daarvandaan richting de Grotten van Hato, het Kabouterbos, het kleine Den Dunki en het topje van de heuvel in Rooi Santu, Seru di Seinpost. Ook het natuurgebied van Jan Thiel kan hier nog bij gerekend worden, en misschien de enkele rooien en stukjes mondi die niet zijn volgebouwd. Voor vogels is de lange overtocht van Oost naar West misschien niet zo dramatisch, alhoewel nooit is aangetoond dat vogels inderdaad van de ene naar de andere kant ‘reizen’. Er is echter ook nooit aangetoond dat dit niet gebeurd. Maar iedereen kan op zijn vingers natellen dat het voor planten en andere diersoorten een stuk moeilijker is. Het Curaçaose witstaarthert, een unicum in het Caribisch gebied, is uitgestorven op Banda Riba en komt alleen nog maar voor in Banda Bou. Verschillende boomsoorten kunnen zich zelfs alleen nog maar verspreiden dankzij het ‘onbewuste’ ingrijpen van de mens. In feite hebben we met z’n allen qua natuur van 1 eiland twee aparte eilanden gemaakt.

Urbanisatie op de eilanden

Op Aruba is dit fenomeen helemaal goed te zien. Het ultra geürbaniseerde eiland heeft stukjes natuur die relatief ver uit elkaar liggen en nauwelijks tot geen contact met elkaar hebben. De Cottontail, het konijntje dat ook op Curaçao voorkomt, en de Sloke of Kuifkwartel een vogel die vooral loopt, raken hierdoor steeds meer geïsoleerd waardoor er weinig interactie is tussen individuen van dezelfde soort en daarmee de soort in gevaar komt door onder andere inteelt. Maar ook andere dieren en planten lijden onder de vorming van deze zogenaamde postzegelnatuurgebiedjes, een term dat in Europa tegenwoordig veel wordt gebruikt.

In de biologie wordt gesproken van zogenaamde corridor gebieden. Dat zijn gebieden die dienen als een soort ‘metro’ voor planten en dieren. Een plek waar ze terecht kunnen om vandaar een sprong verder te maken. Wat daarbij belangrijk is, is dat de afstanden van de corridor gebieden naar de volgende plek niet al te ver zijn. Als soorten zo’n natuurgebiedje niet meer kunnen gebruiken als hub naar de volgende plek omdat de afstand te groot is geworden, verliest het in feite zijn ecologische waarde. Het is ecologisch gezien dan nog maar weinig waard.

Naast het te lijden hebben onder het proces van versnippering van natuurgebieden, lijden onze bossen ook aan verschillende andere factoren:

- vervuiling, door chemische bestanddelen zoals olie;

- ontbossing door het steeds weghalen van stukken mondi voor het bouwrijp maken van terreinen, legaal en illegaal;

- het veranderen van natuurlijke waterstromingen waardoor bij regenbuien er niet genoeg water in het grondwater terecht komt om reserves op te bouwen voor slechte tijden. Vooral het verharden van waterwegen zoals rooien zijn een debacle voor de grondwaterstand;

- de introductie van plantensoorten uit het buitenland die onze eigen bomen en planten wegdrukken of zelfs dood wurgen, zoals de pal’i lechi ((Rubbervine, Cryptostegia grandiflora) die bomen verstikt en de Korona di Hesus (Egyptian balsem, Balanites aegyptiaca), een weinig in het oog lopend maar zeer gevaarlijk oprukkende soort;

- de introductie van diersoorten uit het buitenland zoals de Red Palm Weavil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus) en Agave weavil (Scyphophorus acupunctatus). Niet alleen een gevaar voor net zo buitenlandse dure palmen, maar potentieel ook voor de inheemse Sabalpalm, de enige palmsoort die we van nature hier op het eiland hebben en de Agave weevil voor onze inheemse agaveplanten.

Het feit dat er op Curaçao nog een ‘eiland’ West en een ‘eiland’ Oost is, is een schrale troost. Nijpend wordt het wanneer we ons gaan realiseren dat er zelfs binnen die twee ‘eilanden’ sprake is van fragmentatie en isolatie. Dat we als eilandbewoners zo onbewust overal aan het ‘ontwikkelen’ zijn dat er zelfs binnenin het stukje Banda Bou geïsoleerde natuurgebieden gaan ontstaan die het overleven van de zo bijzondere flora en fauna nog moeilijker maken.

In feite kun je de natuur en alle systemen die daarin functioneren vergelijken met een zeer duur en uniek Perzisch tapijt. In zijn geheel is het tapijt goud waard. Knip het tapijt in stukjes en naai het weer aan elkaar, dan kun je op je kop gaan staan, maar je krijgt er geen cent meer voor. Ook al ben je niets kwijt en heb je het hele tapijt weer bij elkaar. Zo gaat het ook met de natuur. Als het een aangesloten stuk is zonder breuken, dan ‘werkt’ het. Knip je het in stukjes, dan kun je nog zoveel aan elkaar rijgen maar je ‘Perzisch tapijt’ krijg je nooit meer terug.